Investment Styles (Morningstar) and Fund Summary (Yahoo Finance)

Investment Styles (Morningstar) and Fund Summary (Yahoo Finance)In this article, I will show you how to evaluate and compare mutual funds, regardless of the type or objective of the fund. This will help you compare similar mutual funds and decide on which mutual fund best suits your investment needs. This article will be particularly useful for fund evaluators, passive investors, and the average investor looking to purchase a mutual fund. Ultimately, if you practice what is recommended in this article and know what to avoid, you can improve your chances of selecting a great mutual fund.

Mutual funds are investment vehicles that pool money from investors to buy a basket of securities, such as stocks, bonds, money market instruments, and other assets. This basket of securities is then priced and sold to the public on a daily trading basis. These mutual funds are actively managed by professional money managers, meaning their full-time jobs are to allocate the fund's assets to return capital gains and/or income (in the form of dividends and/or interest) for the fund's investors.

In general, mutual funds promise to investors that they can outperform the market (aka the S&P 500 Index), and therefore provide investors with above-average returns (the market average is 10% before inflation). However, this is not always the case, as there are many mutual funds that seek to match or beat the performance of separate indices, such as the S&P 600 Index or the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index (for bond investors). Regardless, the S&P 500 Index is the standard benchmark of the overall U.S. market, to which all other equity investments are compared.

Net asset value (NAV) represents a fund's price per share. Unlike a stock price, the NAV does not change throughout the day, because the buying and selling of a mutual fund occurs only once per day to protect investors from market movements. Instead, a fund's NAV will update at the end of each trading day, after the U.S. markets have closed.

A mutual fund's NAV is very easy to find, but its calculation is shown below:

NAV = (Assets - Liabilities) / Total number of outstanding shares

Below are the main advantages or reasons to purchase a mutual fund:

Below are the main disadvantages or reasons to avoid purchasing a mutual fund:

Now that you have a better understanding of mutual funds, we can look at the different inputs, variables, and measures I use and look at to evaluate any mutual fund. This can be used for comparison purposes as well, which should help you decide on which fund to invest in, if any. A final thing to mention is that when evaluating a mutual fund, you're not looking for "value," this doesn't really apply to mutual funds. Instead, you're just trying to ensure that the fund will beat its respective index and follow the firm's outlined objectives.

Before investing significant capital in a mutual fund, especially one that is not well-recognized, you should closely read the fund's "Prospectus" document (required by the SEC) and go through all the relevant pages on the fund's website. This alone should give you a good idea on the fund's fees and expenses, its past performance, investment holdings, any analysis on performance by the fund's managers, and more.

If you want even more detailed information on a mutual fund, then you can read through the "Semiannual Report" and/or "Annual Report" for the year. Furthermore, the "Statement of Additional Information" (SAI) generally provides even more detail the Prospectus document may have left out, which can be very insightful at times.

In short, this alone is how you evaluate a mutual fund. However, the specifications on what I look for and any shortcuts I use to speed up this evaluation process are discussed later in this article. Moreover, reading the Prospectus is not even necessary until it passes the evaluation process outlined in this article, which can be done entirely through mutual fund research websites.

Besides the mutual fund's website and Prospectus document, below is a list of free-to-use websites and tools I recommend to research and evaluate mutual funds:

I will refer to Morningstar the most, as it's the most (free) comprehensive mutual fund research tool I know of.

One of the first things you should look at when evaluating a mutual fund is to determine what the fund invests in and what investment style the fund follows. Obviously, investors make an investment because they expect some return on their investment, and acknowledge that more risk equals more return potential. Choosing to invest in the right fund that varies in risk and return is therefore key to succeeding with mutual fund investing.

Most mutual funds invest in equity (stocks), fixed-income securities (bonds and money market funds), or a balanced/hybrid mix of the two securities. If you're uncertain of your risk profile or want to learn more about the different mutual funds options out there (with example funds), I highly recommended reading the article linked below.

In short, the mutual fund you choose to invest in largely depends on your investment time horizon, the market, and your goals as an investor. For example, young investors who are generally more risk-prone (aka risk-seeking) would likely choose to invest in a high-growth small-cap equity mutual fund, while someone who expects to retire in the next two years may choose to invest in a bond-heavy (BBB+ rated) mutual fund to preserve their wealth.

Note that the minimum initial investment and whether a fund is closed-ended or open-ended can also limit/restrict some mutual fund investment options for investors.

To understand any fund's objective or investment style, you should look through their website or Prospectus document. Reading the name of a fund and recognizing the type/category of the fund will obviously provide you with some insight as well.

Investment Styles (Morningstar) and Fund Summary (Yahoo Finance)

Investment Styles (Morningstar) and Fund Summary (Yahoo Finance)

More details on the investment style of a fund can also be found under the "Portfolio" tab on a fund's Morningstar page, as shown above for a large-cap growth equity fund and a medium credit risk high-volatility bond fund.

For a quick summary of the fund, you can use Yahoo Finance, search for a fund, and then look at the "Fund Summary" on the right sidebar. This is shown above for VICBX.

Popular mutual fund providers include Fidelity, Charles Schwab, Vanguard, BlackRock, BNY Mellon, among others. If you're investing significant amounts in mutual firms provided by these firms, then you'll likely be a lot more comfortable holding your investment during times of economic turmoil.

What's more important, however, is the management team of a mutual fund. In specific, I try to focus on the five following pieces of information:

In general, you should only invest in mutual funds that have an experienced manager calling the shots, particularly someone with at least five years of experience. However, if a fund has consistently performed well and has a relatively inexperienced manager, then it can be worth considering as the fund manager may have been mentored for several years prior.

Fortunately, Morningstar has simplified this management evaluation process. You can look under the "People" tab on a fund's Morningstar page to see lots of relevant and useful information. Clicking on a manager's name will also offer insight on the manager's industry experience, current funds managed, index performance, and more.

If you invest in a mutual fund, you'll have to pay fees and expenses for these mutual funds to manage and grow your money. These fees are usually depicted in the Prospectus document and on any mutual fund's website. The overall "Class A shares" (as later discussed) expense ratio is displayed on financial data websites (like Morningstar) as well, which most retail investors can use.

The image above is a table describing the fees and expenses of BlackRock's SHSAX Health Sciences Opportunities Fund (found in the fund's Prospectus). This is broken down under the "Price" tab on a fund's Morningstar page as well. As you can see, this mutual fund fee and expense table is divided into "shareholder fees," which are fees paid directly from your investment, and "annual fund operating expenses," which are expenses paid annually as a percentage of the value of your investment.

These line item shareholder fees are described below:

Mutual funds can also exempt these shareholder fees, and these funds are called "No-Load Funds," where there are no fees to buy or sell the mutual fund. Even if a fund is advertised as "no-load," the shareholder fees section could still include exchange fees, redemption fees, service fees, and other random fees that should not be ignored.

Now, let's discuss the annual fund operating expenses:

In summary, mutual fund fees and expenses can be complex and can be overlooked by many investors. If I were to invest in a mutual fund, I would choose one that has a no-load fee with low overall annual fees. If the fund was trying to achieve a specific strategy and could offer higher potential returns, then it may be reasonable to pay a higher fee.

In terms of evaluating a mutual fund, I would trust the expense ratio shown on Morningstar under the "Quote" tab. You can also look under the "Price" tab to see the fund's historical expense ratio percentage, to compare to the category average, to view any other fees, or to see a cost illustration of owning the fund. Personally, I would only read through and examine the fee and expense table in the Prospectus if I were seriously looking to invest in the mutual fund.

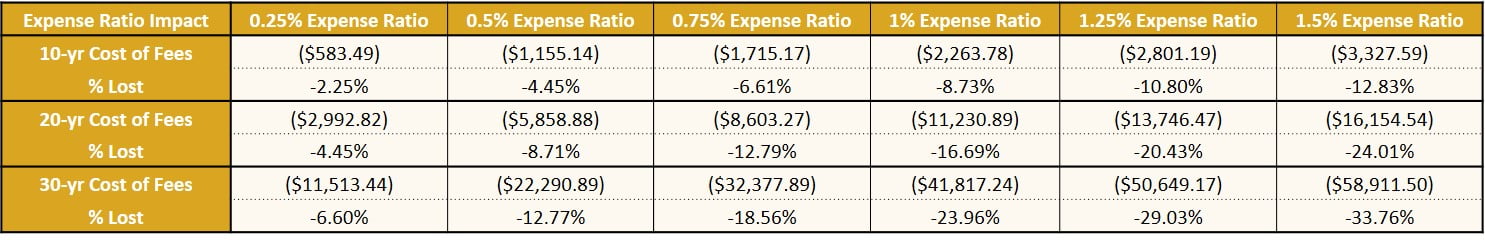

To understand why you should only invest in low-fee mutual funds, see the comparison of realistic mutual fund expense ratios and the amount of money lost over the 10, 20, and 30-year periods, in comparison to the ending value (gross) assuming no fees or expenses whatsoever. The chart and table below begins with an initial investment of $10,000 and assumes an average annual growth of 10% (the average historical rate of the S&P 500):

As you can see, the expenses and fees charged by mutual funds can be quite significant, especially over the long-term when your investment begins to compound and grow more rapidly. Therefore, if you're investing in a mutual fund, ensure the fund is really worth the fee it's charging, or just stick with investing in similar low-fee index funds or ETFs.

You may have noticed there are four columns of mutual fund classes (aka series) for the SHSAX fund, and may have wondered what these are. Although each class invests in the same exact portfolio of securities under the same mutual fund (with the same investment policies and objectives), these mutual fund classes provide different benefits to investors and to the advisors that sell the fund. Each class has its benefits and drawbacks, which the fee and expense table discussed before somewhat covers.

Although there is no standard for how companies use letter designations to differentiate between mutual fund classes, the short and non-extensive list below can generally be followed to understand what each stands for:

Again, it's important to mention that mutual funds can choose to use different letters for their funds. If you need clarification on what a mutual fund class means, then reading through the Prospectus carefully should provide you with this information. However, in most cases you don't have to worry about this as you'll likely be a Class A investor.

The next step is to analyze how the fund has performed historically relative to similar funds. Measuring performance is simply done by measuring the average annual return of the fund. Although this is important, many investors can place too much of an emphasis on a fund's performance. A mutual fund's past performance should only be one piece of the evaluation process, as past performance does not guarantee future performance. Moreover, a top-performing fund in its category did not start as a top-performing fund, it worked its way up until it was recognized as one.

To begin this evaluation, you can look under the "Performance" tab on on a fund's Morningstar page. Here, you will see the returns and any distributions over the 10-year period if you were to invest $10,000 into the fund. It also compares the fund's performance to the index it's trying to beat or match, and the fund's category performance. This is better seen in the tables where you can see the fund's "Percentile Rank" relative to similar funds. Fidelity's "Performance & Risk" tab on any fund's page is also quite helpful to look at. You can also compare the performance of a particular fund with another on both of these websites as well.

Morningstar groups mutual funds into different categories based on the investments they hold, and the funds with the best historical performance are given a four or five star rating, while others are given three stars or below. Morningstar divides this star rating into the 3-yr, 5-yr, and 10-yr periods for comparison purposes, which can be viewed on a fund's page under the "Performance" tab. If a fund has not existed for three years or more, then it will not have a star rating.

An example of a 5-star rated mutual fund is shown below:

The overall star rating shown here is based on a weighted average of the stars given to the fund over the 3-yr, 5-yr, and 10-yr rating periods.

Note that this star rating also considers the amount of risk the fund took on to achieve this return. For instance, if two funds had the same past performance, Morningstar would rate the fund that was the least volatile the highest. In addition, if a fund shows a bigger swing in negative performance relative to its category, their rating will get a penalty of sorts.

In short, this data-driven rating system Morningstar provides is very useful when evaluating a mutual fund's performance. It eliminates average-performing and poor-performing funds and is very useful for comparison purposes when trying to decide on one fund over the other.

Although fund performance is important, ignoring the risk taken to achieve this return is foolish. You cannot evaluate a mutual fund without determining its downside risk. Moreover, if you are to invest in a mutual fund, you should only invest in those that match your risk-tolerance level. Otherwise, you may be inclined to sell your shares prematurely, which may incur a back-end load fee as well.

You should already have a broad understanding of a fund's risk from its star rating, fund name, and fund's investment objective. Obviously, a bond-oriented fund will have much lower risk than an equity growth fund. You can also analyze the fund's holdings, as later discussed. However, for comparison purposes with similar funds, investors can use the "Risk" tab on a fund's page on Morningstar. In short, this is Morningstar's risk-return analysis and volatility measure analysis for a fund, which is compared to the fund's category and index.

The image above is taken from Morningstar's Vanguard's LifeStrategy Growth Fund (VASGX) page, under the "Risk" tab. For reference, this is a balanced fund investing in equity, fixed-income, and international securities. As you can see, over the 10-year period, VASGX has below average risk and above average returns relative to similar funds (aka the category). This "Risk vs. Category" score is measured in terms of how much the fund varied from the monthly returns of similar funds. The "Return vs. Category" is the fund's excess return over the risk-free rate (90 day T-bill), in comparison to similar funds.

On the right half are the Risk & Volatility Measures, as described below (and on Morningstar):

Note that 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year measures for these measures can be found on Zacks Investment Research and Yahoo Finance as well.

The second half under the "Risk" tab provides us with a Risk/Return Analysis (in the image above), which is essentially another visual representation of the risk-return relationship of the fund in comparison to similar funds and the index it's associated with.

On the right half, you'll see Market Volatility Measures. In regards to the Upside Capture Ratio, the fund you're evaluating should always have this value be higher than the index (benchmark) figure of 100. Otherwise, it would likely be much more cost-effective and smarter to just invest in the index fund directly. Ideally, this number should be higher than the Category as well. The last thing you want is for a fund to be staggering in bullish markets.

The Downside Capture Ratio is a measure of how the fund performed in bearish markets relative to the index. Again, if this value is less than 100, then the fund has lost more than the benchmark in market downturns. If this occurs, it could be a sign of incompetent management or the fund not following the objectives it set out in its Prospectus document. It can also be a sign of an overly-aggressive or imbalanced portfolio.

The Drawdown Maximum measures the largest percentage market downturn over a certain time period, in this case from January 1 st to March 31 st in 2020. Again, you want the highest positive percentage value here, unless you're comfortable with the fund having a higher downside risk than the index comparison.

The next step is to examine what the mutual fund invests in, and if applicable, the exposure the fund has to different industries. Note that by this step I'm already aware of the fund's size, its objective, and its risk-return relationship.

In particular, I look at the five following things, which can be viewed under the "Portfolio" tab on Morningstar:

In short, this will give you a good understanding of a firm, its investment objective, and whether it's worth looking into further.

The "Credit Quality/Interest Rate Sensitivity" box measure under the "Portfolio" tab for fixed-income securities (particularly bonds) can give you an idea on the credit quality and volatility of a fund. You can skip this section if you're evaluating an equity fund, or if Morningstar does not provide this for the fund you're researching.

In regards to the Fixed Income Style box, the horizontal axis represents a fund's interest rate sensitivity, determined by the average duration of all the bonds in the fund's portfolio. "Ltd," or limited/short-term bonds are the least volatile as they are least affected by changes in interest rates. On the other hand, "Ext," or extensive/long-term bond funds are the most volatile because of time uncertainty and changes to interest rates. "Mod," or moderate funds experience a volatility somewhere in-between limited and extensive bond funds.

The vertical axis represents credit quality, as determined by the fund's average credit quality of all the bonds in the fund's portfolio. "High" bond funds are low-yield because they own U.S. Treasuries and/or high investment-grade corporate bonds, while "Low" bond funds are high-yield because they own less investment-grade bonds and more junk bonds. "Mid" bond funds therefore fall somewhere in the middle, depending on the fund.

Total assets under management (AUM) describes the amount of assets managed by a mutual fund. This is different from net asset value (NAV), which is simply assets minus liabilities. This AUM figure can fluctuate daily, due to changes in share value and demand for the fund over the course of the day. AUM is important to evaluate, because a larger AUM amount can limit a fund's performance, due to the restrictions and difficulties that come with managing a larger fund.

To elaborate, as mutual funds become larger, they must hold a larger variety of holdings because they cannot have over a certain percentage ownership in a company. In specific, this is described in the Investment Company Act of 1940:

"Under the act, out of 75 percent of a mutual fund's assets, 5 percent or more cannot be invested in a single stock. The fund is also prohibited from acquiring in excess of 10 percent of a single stock's outstanding voting securities. A mutual fund can put that other 25 percent of its investments in a single stock, so it is possible for a fund to invest up to 30 percent of its assets in one stock."

— Zacks Investment Research

In addition to this, it's usually not smart for a company to invest so much of its capital in one security. This can even potentially negatively affect the share price of a small company if a small-cap mutual fund were to invest significant amounts, which is never ideal.

Therefore, although funds with a relatively-high AUM are still able to invest in their top choices, they may have little choice but to invest in less-favorable picks as well. This can also force various funds (e.g., small-cap stock funds) into a different investment style or category. Managers being pressured to buy stocks within the index can even result in large-cap stock mutual funds with a relatively-high AUM, for example, to begin performing too similarly to its respective index.

In short, you can evaluate a mutual fund's AUM and whether it's too small or big by comparing it to similar funds. The fund's performance and overall expense ratio can be very insightful too. This is because a high AUM and high turnover rate (discussed below) can mean higher trading transaction costs for the fund, which can reduce investment returns. Therefore, these two should be looked at together.

The turnover rate is how often securities within the fund are being bought and sold over the past year, and is therefore a gauge on how active the fund is. In general, highly active managed funds (e.g., growth funds) will have higher turnover rates than less actively managed funds (e.g., index funds, value funds, fixed-income funds, etc). If a fund has a turnover rate of 50%, then this means the fund has had 50% of its holdings be replaced over the past 12 months.

Investors should avoid investing in funds with high turnover rates, as this means increased fund expenses and even negative tax consequences. This is because fund's have trading costs, and any costs for security turnover is taken from the asset's funds which can increase the fund's expenses. Moreover, if investors are not in a tax-advantaged account, any short-term capital gains tax from high turnover rate funds will be distributed to investors, which investors may then have to pay taxes on.

If you're investing in high-growth mutual funds, it's not uncommon to see this turnover rate over 100%. In this case, you should look to see if the fund's performance makes up for the additional fund expenses and taxes you may be receiving. Additionally, you can compare the fund's turnover ratio to similar funds as well.

It goes without saying that you should invest in the most tax-efficient mutual fund. The most tax-efficient funds are those with a low rate of turnover, as previously discussed, and those that generate little to none in dividends, interest, and/or capital gains distributions. This can sometimes include small-cap funds, value funds, and growth funds as well, but you'll have to examine their turnover rate.

Index funds and municipal bond funds, in particular, are the most tax efficient. This is because index funds are passively managed and municipal bonds, by nature, are normally exempt from state and federal income taxes. Funds that are not tax-efficient include large dividend funds and bond-heavy funds, because interest and dividends received are subject to being taxed. Therefore, if you're investing in a fund for its income, try to invest in the most tax-efficient fund.

On Morningstar, you can look under the "Price" tab to see the "3-Year Tax Cost Ratio," which is a measure of how much a fund's annualized return will be reduced by the taxes investors pay on distributions (i.e., from stock dividends, bond interest, and capital gains). If a fund has a tax cost ratio of 1% for the 3-year period, then on average each year, investors lost 1% of their assets in the fund to taxes. Therefore, the higher this ratio (under the "Fund" text), the more tax costs investors will receive. This ratio can also be compared to the category average.

Yield is something income investors should always look into, as this can be much of the return they will receive from their investment. This includes any fixed-income (bond) and dividend-oriented mutual funds. As you may know, the higher a fund's yield, the more risk and return you are expected to receive. Yield is also highly dependent on the Federal Reserve's actions with interest rates. For example, if the Fed is lowering interest rates, the yields on mutual funds that hold stocks and bonds will also decline.

TTM yield (aka distribution yield) refers to the percentage of income (interest and dividend payments) a fund has distributed to investors over the last 12 months. It's the yield you're going to get today if you invest in the mutual fund, and can be found under the "Quote" tab on a fund's Morningstar page. More details on a fund's distributions can be found under the "Performance" tab as well.

For reference, the TTM yield formula is below:

TTM = Income / (NAV + Capital gains)

where:

Although the TTM, a backwards-looking figure, can give you an overall picture on a fund's annual distributions, it's not the most useful for comparison purposes. This is because of the possibility of special dividends, yield fluctuating due to the market, and the possible inclusion of capital gains distributions. Therefore, the TTM should be viewed alongside the 30-day SEC yield to accurately evaluate a fund's expected yield.

The 30-day SEC yield (aka standardized yield) is the percentage of income a fund distributes as income (dividends and interest) over the most recent 30-day period, following an SEC-mandated yield calculation formula. The 30-day SEC yield is a conservative estimate on how much income investors can expect to earn over the course of a 12-month period, assuming the fund maintains the same rate for the rest of the year. In other words, it's a projected estimate of earnings that income investors can use to estimate their annual yield.

Although Morningstar does not provide a 30-day SEC yield figure on their fund's pages, you can refer to the fund's website or use a website like Zacks Investment Research where it should be displayed.

You can also calculate the 30-day SEC yield using the formula below:

30-day SEC yield = 2 * (((a - b) / (c * d) + 1) 6 - 1)

where:

I typically prefer the 30-day SEC yield for comparing funds over the TTM yield, as it's a legal standardized requirement, a forward-looking indicator, and focuses on actual income earned (ignores capital gains). However, this figure may not work well for funds that do not payout regularly monthly distributions, as it's only a 30-days estimate figure -- so keep this in mind.

For dividend-oriented mutual funds, where investors expect much of their income to come from regular dividend payments, the dividend yield can be evaluated alongside the TTM yield and 30-day SEC yield. This can be found on the "Style Measures" table, under the "Portfolio" tab on a fund's Morningstar page.

Dividend yield can also be calculated using the formula below:

Dividend yield = Annual dividends / Current share price

What Morningstar and this formula provides is the TTM dividend yield. Much like bond yield, higher dividend yield means higher return and risk. Generally, it's wise to stay within the 2-5% range for dividend yields, although this can also depend on the market.

In summary, to evaluate and compare a mutual fund, become comfortable with using Morningstar as your main tool and understand the different factors that can make a bad, average, or great investment. Additionally, if you're making a big or long-term investment, then it's best to spend time reading through the fund's Prospectus document as well.

Unfortunately, many mutual funds can quickly become unattractive and costly options for investors, and can be largely overshadowed by ETFs and index funds. Moreover, mutual funds can be daunting to research and understand, which this lengthy article makes clear. Regardless, mutual funds come in many types, and spending time evaluating a mutual fund can be worthwhile over the long-term.

Unlock smarter investing with StableBread's Automated Stock Analysis Spreadsheet. Effortlessly analyze company fundamentals, financial statements, and valuations. No manual data collection required.